Monte Report for May 2006

As some of you have already heard, the month of May involved some drama. The melodramatic version is that I got taken to the psychiatric ward against my wishes, by the police, handcuffs and all. This occurred as a result of an appointment with my thyroid doctor which took place just an hour or two after an incident of me cutting my arm. The less-dramatic (but more accurate) version of the tale is that my thyroid doctor overreacted, and chose to take the conservative approach by contacting the police, even though I indicated that I didn't think it was necessary. Normally, I would have been held for 72 hours to help ensure that I returned to a more stable space. As it turned out, by the time I got to the hospital I already WAS in a more stable space, and my self-inflicted injury was clearly very minor (physically). After much questioning by the hospital experts, they agreed that I would be better off over the ensuing 72 hours if I was left to my own devices. And they were correct. I had a number of plans on tap for those 72 hours, including dinner with a good friend later that day, lunch the following day with another good friend, and then off to my parents' house for a weekend with family to celebrate my birthday and see an Aunt and Uncle visiting from out of town.

My birthday was marked with the traditional Rhubarb Birthday Thing-Cake.  I also saw two really good birds in my parents' yard on my birthday: a Band-tailed Pigeon (photo courtesy of Vicki Rogers) and a Barn Owl (photo courtesy of Captain Chickenpants).

I also saw two really good birds in my parents' yard on my birthday: a Band-tailed Pigeon (photo courtesy of Vicki Rogers) and a Barn Owl (photo courtesy of Captain Chickenpants).  I also spontaneously repeated an event from my outrageous birthday celebration last year, thus beginning what could become another tradition: Tequila Shots! The "event" was kicked off once again with my karaoke-style rendition of Shelly West's song "Jose Cuervo."

I also spontaneously repeated an event from my outrageous birthday celebration last year, thus beginning what could become another tradition: Tequila Shots! The "event" was kicked off once again with my karaoke-style rendition of Shelly West's song "Jose Cuervo."  Then, with a brand new bottle of Silver Patron, I was joined by six family members doing the salt/shoot/lime thing -- a first for a number of them!

Then, with a brand new bottle of Silver Patron, I was joined by six family members doing the salt/shoot/lime thing -- a first for a number of them!  It was a lot of fun.

It was a lot of fun.

One strangely anti-climactic thing occured on May 5th and which could have had some sort of impact on me - both positive and negative. As some of you know, I have been actively pursuing employment elsewhere -- not just anywhere, though: for the past couple years I have been pursuing a very specific position with a very specific organization. (I would rather not mention what that job is or the organization.) I did a lot of research about the job, spent months preparing my application (the application form was more than thirty pages long) and finally submitted it. I apparently made it past the first cut -- but on May 5 I was notified that my application had been eliminated from further consideration. It took me a while to figure out what sort of reaction I had. Certainly, there was some disappointment -- after expending so much effort in pursuit of a job that I think I would be perfect for, I would have thought they'd at least counter-offer with some other similar position within their organization. But, at the same time, there was relief to finally have closure on that particular dangling issue. And I was also able to pat myself on the back (and accept pats on the back from others) for having had the nerve to pursue the position in the first place. Naturally, I assume that my mental health played a role in their decision. Though I'm not sure how legal that is, I wouldn't have wanted to conceal what is probably my biggest weakness, and one which they would be sure to encounter eventually anyway. So, for better or worse, that sub-chapter of my life is now finished.

In general, and despite the various difficulties I faced this month, I have actually made a significant amount of progress. I have been aggressively pursuing modes of thinking and types of support that will allow me to work towards resuming full-time work in a safe and sustainable manner. As I learn more and more about the roots of my illness, I am better able to understand why my triggers are so powerful. This increasing level of understanding has a positive effect on the guilt and shame that I feel for the imposition my disease has on the people in my life. Despite the encouragement I receive at work to think of my illness in the same way as we think about a bad case of the flu or a nasty cold when considering whether I need to call in (or go home) sick, the fact remains that I have a very difficult time doing so without feeling like I'm letting my coworkers down by having failed to keep my depression under control -- or for allowing a series of triggers to overpower me. But progress is being made, and one day early this past week I managed to go home after working just one hour, when my anxiety level was skyrocketing for some reason. It was quite difficult to say, "I need to go home," and I apologized a pathetic number of times for needing to leave. But in the end it was obviously the right thing to do, and I was on a much more even keel for the remainder of the week. Overall, despite the cutting episode, and despite the fact that the first week of May was especially difficult, the month as a whole is the best I've had since last October by nearly every measurement. I have switched to a new psychiatrist -- one who is significantly more familiar with the type of medication that I am on -- and he has prescribed a "mood stabilizer" as an adjunct to my regular antidepressant. (He is also the one who recommended Cod Liver Oil.) It's probably too early to tell if the new medication is helping yet, but I'm feeling optimistic about it. Anyway, I'm hoping that my June Report will indicate significant positive changes -- such as a clear plan to return to full-time work and a marked decrease in difficult days and susceptibility to triggers.

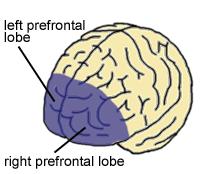

One of the ways my understanding of depression is growing has to do with the biological responses within the brain to stimuli -- stimuli such as inter-personal interactions, observations of particular things or events, and mere memories that pop into my head seemingly at random. In particular, I'm learning all about the functioning of the pre-frontal cortex and the limbic system.

This sort of thing was certainly touched on when I was in the hospital in 2003, but it is becoming much clearer the more I read about it -- and this is really helping me to step back and be an observer of myself when my brain is rebelling. Here are a couple of quotes from Dr. Allen's book Coping With Depression:

This sort of thing was certainly touched on when I was in the hospital in 2003, but it is becoming much clearer the more I read about it -- and this is really helping me to step back and be an observer of myself when my brain is rebelling. Here are a couple of quotes from Dr. Allen's book Coping With Depression:

[R]esearchers are now linking major depression to compromised funtioning of the pre-frontal cortex, an area of the brain that not only regulates emotional distress, but also plays a prominent role in executive functioning - deliberating, planning, decision-making, and complex problem solving. [p 46]

and

Evidence of changes in amygdala activity [within the brain's "limbic system"] demonstrates most directly how depression is a high-stress, high-anxiety state. . . . [T]he amygdala rapidly responds to threatening situations and orchestrates fear responses. . . . The magnitude of abnormal amygdala activation in depression is substantial . . . [p 144]

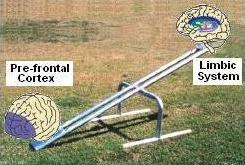

An analogy came to mind as I read the details about the hormones and neurotransmitters etc that come and go in response to stress, and how they activate or deactivate different parts of the brain. Imagine a teeter totter. Typically, a teeter totter that's not in use has one end on the ground - one end is heavier than the other. In our brain, the pre-frontal cortex and the limbic system do teeter-totter-like dance where only one can be in the lead a time. Think of the end of the teeter totter that's on the ground as the part that is in control. With our brains, the end that is usually "in control" is the pre-frontal cortex - the part where we think, deliberate, reason, regulate our emotions, and so on. However, in the course of mammalian evolution, an area of the brain which we call the limbic system evolved to kick in and override the pre-frontal cortex when danger suddenly appeared - like the Neanderthal that comes home to the cave from a day out hunting only to discover a saber-toothed tiger inside and finds himself (or herself) engaged in manual combat with the animal in order to keep it from eating the children or stealing the gazelle we just caught, thus leaving the family without food.

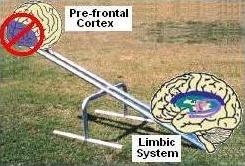

Think of the end of the teeter totter that's on the ground as the part that is in control. With our brains, the end that is usually "in control" is the pre-frontal cortex - the part where we think, deliberate, reason, regulate our emotions, and so on. However, in the course of mammalian evolution, an area of the brain which we call the limbic system evolved to kick in and override the pre-frontal cortex when danger suddenly appeared - like the Neanderthal that comes home to the cave from a day out hunting only to discover a saber-toothed tiger inside and finds himself (or herself) engaged in manual combat with the animal in order to keep it from eating the children or stealing the gazelle we just caught, thus leaving the family without food. In such a situation, controlled reasoning and deliberation will give the saber-tooth plenty of time to eat you. As mammals evolved, those whose limbic systems could kick into high gear the fastest tended to survive, while their "slower" kin got et up. And as soon as the danger was past, the pre-frontal cortex would reassert control, and the hormones and neurotransmitters necessary for turning the limbic system "off" again would begin to circulate. So, when necessary, the limbic system side of the teeter totter bounces down to the ground, and then in short order rises back into its stand-by position as the pre-frontal cortex drops back down and resumes its dominance. In the course of our evolution, there was generally no need for constant activation of the limbic system. If a saber-tooth moved into your cave and wouldn't leave, you just found a new cave -- you didn't spend the next six months trying to share your cave with something that wants to eat you. As human society has evolved, however, extended periods of stress have become commonplace. Depending upon the resiliency of one's brain (think of it as one's "temperament"), one may begin to lose the ability to de-activate the limbic system once the danger has passed. Or, further complicating matters, the limbic system may become hyper-sensitive to threats, to the point where it kicks into gear even when no real threat actually exists. The Post Traumatic Stress Disorder commonly experienced by combat veterans is the classic example of the brain going into "emergency mode" at the mere suggestion or reminder of what, in the distant past, really was an extreme danger. In these situations, the teeter totter tips to the other direction and the limbic system side stays in the dominant position -- leaving one in a state that is essentially one of fear and high anxiety, even if in reality there is no danger at all. From this perspective, depression (and anxiety and a number of other mood disorders) can be seen as essentially a mechanical (or chemical/biological) problem -- and therefore absolving the sufferer from responsibility, just as we would absolve, say, a blind person from being responsible for their lack of sight. But there's a significant difference: you can't "think" your way out of blindness or most other disabilities that are strictly physical. The brain, however, does respond to "thinking" -- the chemicals circulating in the brain can often be influenced by conscious thought -- or at least nudged in the right (or wrong) direction. Provided the "damage" isn't so severe as to be entirely irreversible, one can "exercise" the brain in such a way as to increase the strength of the pre-frontal cortex, and to quell the hyperactivity of the limbic system. This is clearly easier said than done -- especially when the limbic system is actively out of control. Right now, as I write this, my limbic system is asleep, and I'm in a pretty good mood - I've got NPR playing on the radio, I'm looking forward to laying out on the patio with a good book, the Black-headed Grosbeaks are still gracing my feeder with their beautiful colors and beautiful song (blurry photo by me)

In such a situation, controlled reasoning and deliberation will give the saber-tooth plenty of time to eat you. As mammals evolved, those whose limbic systems could kick into high gear the fastest tended to survive, while their "slower" kin got et up. And as soon as the danger was past, the pre-frontal cortex would reassert control, and the hormones and neurotransmitters necessary for turning the limbic system "off" again would begin to circulate. So, when necessary, the limbic system side of the teeter totter bounces down to the ground, and then in short order rises back into its stand-by position as the pre-frontal cortex drops back down and resumes its dominance. In the course of our evolution, there was generally no need for constant activation of the limbic system. If a saber-tooth moved into your cave and wouldn't leave, you just found a new cave -- you didn't spend the next six months trying to share your cave with something that wants to eat you. As human society has evolved, however, extended periods of stress have become commonplace. Depending upon the resiliency of one's brain (think of it as one's "temperament"), one may begin to lose the ability to de-activate the limbic system once the danger has passed. Or, further complicating matters, the limbic system may become hyper-sensitive to threats, to the point where it kicks into gear even when no real threat actually exists. The Post Traumatic Stress Disorder commonly experienced by combat veterans is the classic example of the brain going into "emergency mode" at the mere suggestion or reminder of what, in the distant past, really was an extreme danger. In these situations, the teeter totter tips to the other direction and the limbic system side stays in the dominant position -- leaving one in a state that is essentially one of fear and high anxiety, even if in reality there is no danger at all. From this perspective, depression (and anxiety and a number of other mood disorders) can be seen as essentially a mechanical (or chemical/biological) problem -- and therefore absolving the sufferer from responsibility, just as we would absolve, say, a blind person from being responsible for their lack of sight. But there's a significant difference: you can't "think" your way out of blindness or most other disabilities that are strictly physical. The brain, however, does respond to "thinking" -- the chemicals circulating in the brain can often be influenced by conscious thought -- or at least nudged in the right (or wrong) direction. Provided the "damage" isn't so severe as to be entirely irreversible, one can "exercise" the brain in such a way as to increase the strength of the pre-frontal cortex, and to quell the hyperactivity of the limbic system. This is clearly easier said than done -- especially when the limbic system is actively out of control. Right now, as I write this, my limbic system is asleep, and I'm in a pretty good mood - I've got NPR playing on the radio, I'm looking forward to laying out on the patio with a good book, the Black-headed Grosbeaks are still gracing my feeder with their beautiful colors and beautiful song (blurry photo by me) and I just wrapped up a week at work that was filled with good connections with many of the people I feel closest to there. But two weeks ago when I found myself cutting my arm, my pre-frontal cortex had all but abandoned me while my limbic system raced along at 90 mph in first gear. For all intents and purposes I was essentially insane, albeit temporarily.

and I just wrapped up a week at work that was filled with good connections with many of the people I feel closest to there. But two weeks ago when I found myself cutting my arm, my pre-frontal cortex had all but abandoned me while my limbic system raced along at 90 mph in first gear. For all intents and purposes I was essentially insane, albeit temporarily.

My challenge is not so much figuring out how to avoid cutting myself in the future, but rather the challenge is figuring out how to recognize when I'm suddenly heading down that path towards extreme irrationality so that I can immediately take evasive maneuvers. Once I've fallen into the Pit of Despair, my "agency" is so constrained that I am hard pressed to do anything helpful on my own behalf. I have a feeling that I've been paying too much attention on methods for coping when I'm in that Pit, and not enough attention on the task of changing directions when triggers are first beginning to rapidly accumulate and therefore making a fall down into the Pit dangerously imminent.